In anticipation of a solo exhibition by artist Nardo at Bitcoin Mena, in collaboration with AOTM GalleryI sat down with him to explore the intersections of memes, mythologies, and digital culture. Nardo’s work navigates the intriguing space between the tangible form of traditional painting and the ephemeral nature of meme culture – two seemingly contrasting media evolving alongside Bitcoin.

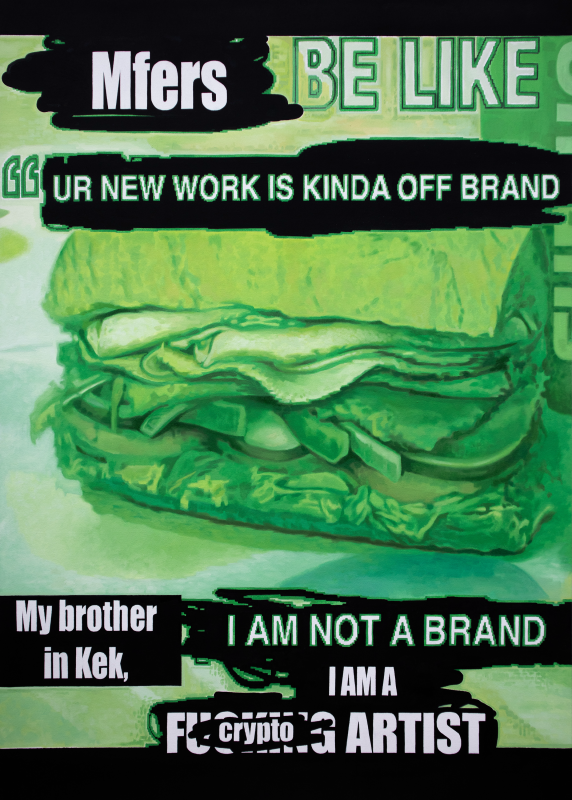

The title of your exhibition, Fresh Impact, and the central painting, Sandwich Artist, both reference Subway-related memes. Notably, in 2013, Subway became the first fast-food chain to accept bitcoin — a moment documented by Andrew Torba, who famously used bitcoin to buy a $5 sub in Allentown, Pennsylvania (an ironic detail, considering that Torba is now CEO of social media). network Gab). This early mix of Bitcoin and meme culture led to humorous reflections on “spending generations’ wealth” on money and highlighted themes of currency value over time, as the dollar’s purchasing power declines while Bitcoin’s grows. How does this Subway meme resonate with you, and how does it shape your approach to painting in an increasingly digital age?

I think there’s something to be said about fast consumption in today’s culture – whether it’s fast food footlong subs or internet memes. The attention span of the human senses has dwindled to bursts of repetitive dopamine, where selecting your type of bread, meat and fillings becomes the most exciting part of your afternoon. Then comes the tireless effort to finish 12 inches of processed food. You repeat this over and over again because it suits you, and maybe next time you’ll thrill yourself by swapping cheddar for provolone.

However, Subway has developed a systematic experience that feels eternal. Memes and internet behavior function in a similar way. The momentary consumption of entertaining or humorous memes acts as the dopamine hit: we share them with friends, they spread at high speed, and then they often die, leaving us on to the next one. Yet the success of memes also lies in their systems: cultural iconography, bold fonts on top of captivating images, hyper-sharp visuals, fried aesthetics, or low-effort applications. Memes depend on visual and cultural layers: bread, meat and toppings.

I think when it comes to Bitcoin, we really need to confront its experiential nature at the exact moment of the exchange. To have bought a footlong worth $5 worth of Bitcoin in 2013, to see it today in 2024 as ~$4,300 is both absurd and somewhat painful, but the experience is everlasting. The very act of using digital internet money in exchange for physical, consumable goods feels almost alchemical.

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “memes” to describe units of cultural transmission, likening their spread to gene replication. Memes also resemble viruses in the way they spread through social networks, blurring the lines between genes and viruses, as both can integrate into DNA and influence evolution. You and I have joked that memes – and memecoins – are akin to the fast food of digital culture, serving as cybernetic junk food or street drugs. Do you consider memes a low art form? Is the accumulation of studio detritus made famous by painter Francis Bacon, or the bizarre detritus and detritus of Dash Snow’s 2007 “hamster nest” installation, somehow related? What do you think of contemporary artists like Christine Wang, who replicates remarkable memes in her recent painting exhibition ‘Cryptofire Degen’ at The Hole in New York? What happens when a digital meme becomes a physical painting?

This all ties into what I discussed earlier: I’m interested in slowing down the consumption process. It can be a little jarring to painstakingly hand-paint a meme in oil and present it as such. Likewise, considering waste as form or content, rather than as something to be thrown away, fascinates me.

What’s left after the user has eaten their lunch and scrolled through countless memes on Twitter? The whole experience can feel like the undoing of brain rot – a reduction of structure and existence within passive chaos. But perhaps that’s the liminal mentality needed to produce the most viral ideas.

My introduction to cybernetics came from Japanese animated series like Ghost in the Shell (1995-2014), which explored cyberpunk themes like internet-connected ghosts, hackers, and cyberviruses, echoing Dawkins’ ideas about memes and cultural transmission. The series highlights concepts such as ‘ghost hacking’ and ‘thought viruses’, which multiply in networks and influence societal behaviour, in line with Dawkins’ idea of self-replicating cultural units. Given your recent exploration of the “skibidi toilet” meme phenomenon, what insights have you gained about how this meme has spread through social networks and shaped the collective consciousness of younger audiences?

The Ghost in the shell connection is not far removed from the world as we know it today. Like the premise of that “fiction,” our fleshy brains are nested in a cybernetic facade of digital personas and communications. We practically live vicariously through a digitized shadow self – a projection of what we think we can become. This goes along with why I often say, “You become what you meme.”

I’m deeply intrigued by the phenomenon of American youth becoming obsessed with new memes that older generations can’t fathom, like Skibidi toilet. I think it is in this rupture of sensibility that new languages are born, while old mythologies are repackaged in contemporary ways. Skibidi toilet is the Iliad from the internet.

In addition to Ghost in the Shell’s exploration of cybernetics, the groundbreaking anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion intersects the Age of Aquarius concept through the themes of interconnectedness and collective consciousness. The series delves into the merging of individual identities and reflects how hive mind behavior in today’s internet culture reflects the rapid influence of shared information and memes. In your artwork Sandwich Artist you highlight the tension between individual artistry and the pressure that comes with representing an anonymous brand. How have you observed this shift over time, and how can artists engage with collective ideas while maintaining their individuality in today’s digital culture?

The Sandwich artist piece uses a well-known meme template, but through various digital modifications – especially the literal scribbling of pre-existing text – it takes on the look of graffiti and ultimately becomes my own. I like this piece because it represents an individual manifesto of my work and reflects how I feel about my artistry as a whole. Sure, consistent branding and aesthetics are great for sales when done right, but I’m more interested in how my work exists within a long enough historical timeline. The hive mind longs for a brand it can rally behind, but history longs for individual artistry.

We’ve discussed the term “subway” in relation to submarine sandwiches, but it also conjures up the idea of underground transportation. Japan has famously studied mycelium growth patterns to optimize its subway and train systems. Like fungi, memes spread and connect individuals in a vast, decentralized network, evolving as they move from one “host” to another. This fungal comparison highlights how memes dynamically adapt and spread, reflecting natural systems of growth and communication. How do you think artists can consciously navigate this memetic landscape of reproduction, host vessels, and network dynamics?

The lifespan of most Internet memes moves so quickly that it’s hard to catch them before they fade into a shallow grave. Of the few who manage to take control of the collective consciousness, I find it fascinating to analyze how they are connected to humanity’s past on a metaphysical level. Trends and symbols have remained consistent throughout human history; they simply emerge in different forms as time passes.

Efficient memes depend on efficient information delivery systems. As artists, we must remain aware of history and metaphysical symbolism, as this awareness can help us uncover our own original selves through the mirror of memes.